Being unemployed in the US after the Obama presidency

First posted on Tim Vlandas' website

Obama was elected in 2008 during the height of the crisis with

much expectations that he would improve the conditions of the least

well-off in American society. As his term nears its end, I use the

latest OECD data to assess how unemployed individuals fare now compared

to both other developed countries and to when he started his term.

In a nutshell, I show that in all plausible scenarios, individuals in the initial phase of unemployment are worse off in the US than in a median OECD or EU country and their relative situation has gotten worse since 2007, especially if they are in the middle class.

The OECD tax-benefit Model allows you to specify the marital situation of the family (single, one earner married couple, and two earners married couple) and whether they have children (in this case no children versus two children) for different levels of the average wage.

For simplicity I show the replacement rate for a case when the family does not qualify for cash housing assistance or social assistance in either the in-work or out-of-work situation. I also do not consider the case of earners with 150% of average wage.

Comparing different family and income situations reveals that the US is least generous compared to the OECD and EU median for ‘middle class’ (100% of average wages) families that are composed of lone parents with 2 children. The next biggest gap between the US and the OECD/EU median is for low income families with either one earner couple or a lone parent.

By contrast, low income families (67% of average wage) with two earners with or without two children would fare almost exactly the same in terms of replacement rate in the median OECD and EU country as in the US.

Figure 1: The difference between the US and the EU/OECD average replacement rates in 2014

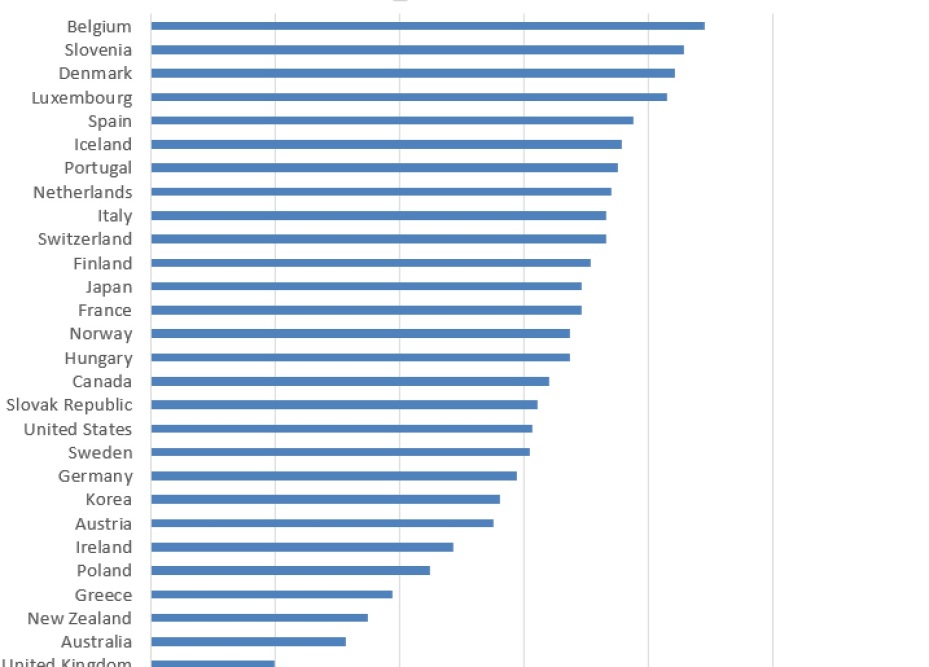

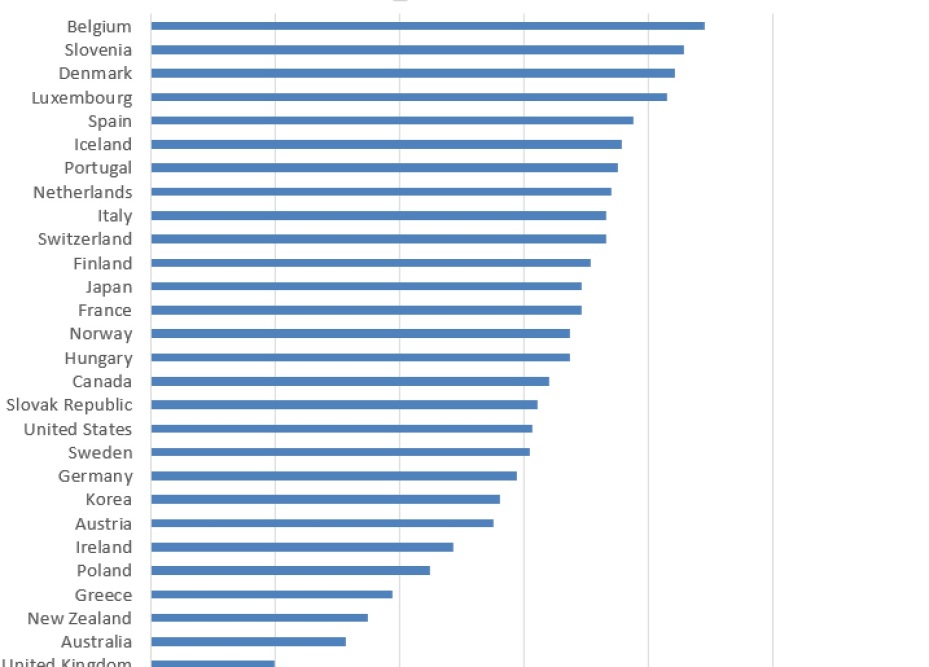

Figure 2: 2014 replacement rate for a single earner with no children that does not qualify for cash housing assistance or social assistance and had previous earnings of 67% AW

Figure 3 shows how the gap between the US and the EU has evolved between 2007 and 2014 for different family-income scenarios. Positive values indicate that there has been an increase in the gap between what a person would get in a median EU country and what they would get in the US. Thus for instance, we see that the biggest increases in the gap has been for one earner married couple with no children that earned 100% of the average wage prior to becoming unemployed and a single person with no children also earning 100% of the average wage prior to becoming unemployed. The next biggest increase has occurred for a lone parent with two children.

Thus, over the Obama presidency, the welfare of vulnerable middle class families in the US relative to their counterpart in the Europe has gotten worse. This is a striking result given the significant retrenchment of European welfare states that has taken place in Europe between 2008 and 2014 (the period under consideration here).

Figure 3: The difference between the EU-US gap in 2007 and in 2014

As Rehm brillantly discusses in his latest book “Risk inequality and Welfare state“, countries with concentrated risks of unemployment among low income workers are less likely to exhibit pro-welfare state cross-class coalitions. At the same time, the US type of capitalism limits the power of the unions while making it unlikely that employers will consent – in the words of Korpi – to more generous social policies (see Varieties of Capitalism literature).

As a result, where there is no clear efficiency imperative (e.g. Obamacare in the context of objective inefficiencies in the health care sector in the US), it is therefore difficult even for a left leaning government to undertake an expansion of welfare state policies.

In a nutshell, I show that in all plausible scenarios, individuals in the initial phase of unemployment are worse off in the US than in a median OECD or EU country and their relative situation has gotten worse since 2007, especially if they are in the middle class.

OECD data

The OECD has data on the net replacement rates for six family types in the initial phase of unemployment. The latest data available is 2014 so it is in principle plausible – though unlikely – that the situation has improved massively in the last two years and that this is not captured by my data. Note further the emphasis on the initial phase of unemployment: after a certain time in unemployment – which varies by country – unemployed lose eligibility to certain benefits (or experience falls in the replacement rate).The OECD tax-benefit Model allows you to specify the marital situation of the family (single, one earner married couple, and two earners married couple) and whether they have children (in this case no children versus two children) for different levels of the average wage.

For simplicity I show the replacement rate for a case when the family does not qualify for cash housing assistance or social assistance in either the in-work or out-of-work situation. I also do not consider the case of earners with 150% of average wage.

The situation in 2014

Figure 1 shows the difference between the US and the EU/OECD average replacement rates in 2014. As an example consider the case of a single person with no children earning 67% of the average wage prior to becoming unemployed. In the US, the person would get 61% out of work income as a percentage of previous earnings equal to 67% of the average wage. The equivalent OECD median is 65% while the EU median is 68% so the gap between the US and the OECD median is 4 percentage points while it is 7 percentage points between the US and the EU.Comparing different family and income situations reveals that the US is least generous compared to the OECD and EU median for ‘middle class’ (100% of average wages) families that are composed of lone parents with 2 children. The next biggest gap between the US and the OECD/EU median is for low income families with either one earner couple or a lone parent.

By contrast, low income families (67% of average wage) with two earners with or without two children would fare almost exactly the same in terms of replacement rate in the median OECD and EU country as in the US.

Figure 1: The difference between the US and the EU/OECD average replacement rates in 2014

Cross-national variation

In Figure 2, I show the 2014 cross-national variation in the replacement rate for a single earner with no children that does not qualify for cash housing assistance or social assistance and had previous earnings of 67% of average wage. This reveals that the US is not the worse country among developed countries (the worse is not surprisingly the UK – though note that the situation does not quite look as dire for the UK if the family qualifies for cash housing assistance). But it is located in the bottom half of the ranking.Figure 2: 2014 replacement rate for a single earner with no children that does not qualify for cash housing assistance or social assistance and had previous earnings of 67% AW

Changes since 2007

In 2014, the average across all family types and both income situations for the US is 59% compared to 70% for the OECD median and 71% for the EU median. This represents a fall from 2007 where the average was 62% for the US, 60% for the OECD and 71% for the EU median.Figure 3 shows how the gap between the US and the EU has evolved between 2007 and 2014 for different family-income scenarios. Positive values indicate that there has been an increase in the gap between what a person would get in a median EU country and what they would get in the US. Thus for instance, we see that the biggest increases in the gap has been for one earner married couple with no children that earned 100% of the average wage prior to becoming unemployed and a single person with no children also earning 100% of the average wage prior to becoming unemployed. The next biggest increase has occurred for a lone parent with two children.

Thus, over the Obama presidency, the welfare of vulnerable middle class families in the US relative to their counterpart in the Europe has gotten worse. This is a striking result given the significant retrenchment of European welfare states that has taken place in Europe between 2008 and 2014 (the period under consideration here).

Figure 3: The difference between the EU-US gap in 2007 and in 2014

Disappointing but not surprising

While disappointing, the falling welfare of the unemployed in the US is not entirely surprising from a theoretical perspective. The welfare state literature makes clear that liberal welfare regimes’ structure (e.g. targeted means tested benefits) limit the popular support for generous welfare state benefits for the unemployed that are seen as particularly undeserving.As Rehm brillantly discusses in his latest book “Risk inequality and Welfare state“, countries with concentrated risks of unemployment among low income workers are less likely to exhibit pro-welfare state cross-class coalitions. At the same time, the US type of capitalism limits the power of the unions while making it unlikely that employers will consent – in the words of Korpi – to more generous social policies (see Varieties of Capitalism literature).

As a result, where there is no clear efficiency imperative (e.g. Obamacare in the context of objective inefficiencies in the health care sector in the US), it is therefore difficult even for a left leaning government to undertake an expansion of welfare state policies.

Comments